The Bank of Sturgeon Bay

[Midwestern readers can skip to the paragraph below the encased cent.]

Door County is the thumb of Wisconsin. It juts into Lake Michigan and forms the east side of the bay of Green Bay. It sits atop a dolomite structure known as the Niagara escarpment, the geological formation that is responsible for Niagara Falls. The county takes it name from Death’s Door, the strait that lies between the northern end of the peninsula and Washington Island. The waterway was given this name by the French (Porte des Morts) due to its treacherous currents.

The largest city and county seat is Sturgeon Bay. The county’s position on Lake Michigan gave it a long maritime tradition. Lighthouses dot the shoreline. Shipbuilding, fishing and agriculture were the most significant early industries. While all these still exist in the county, tourism has become the primary economic engine. The county’s population is about 27,000 but swells to a quarter million during the summer tourist season.

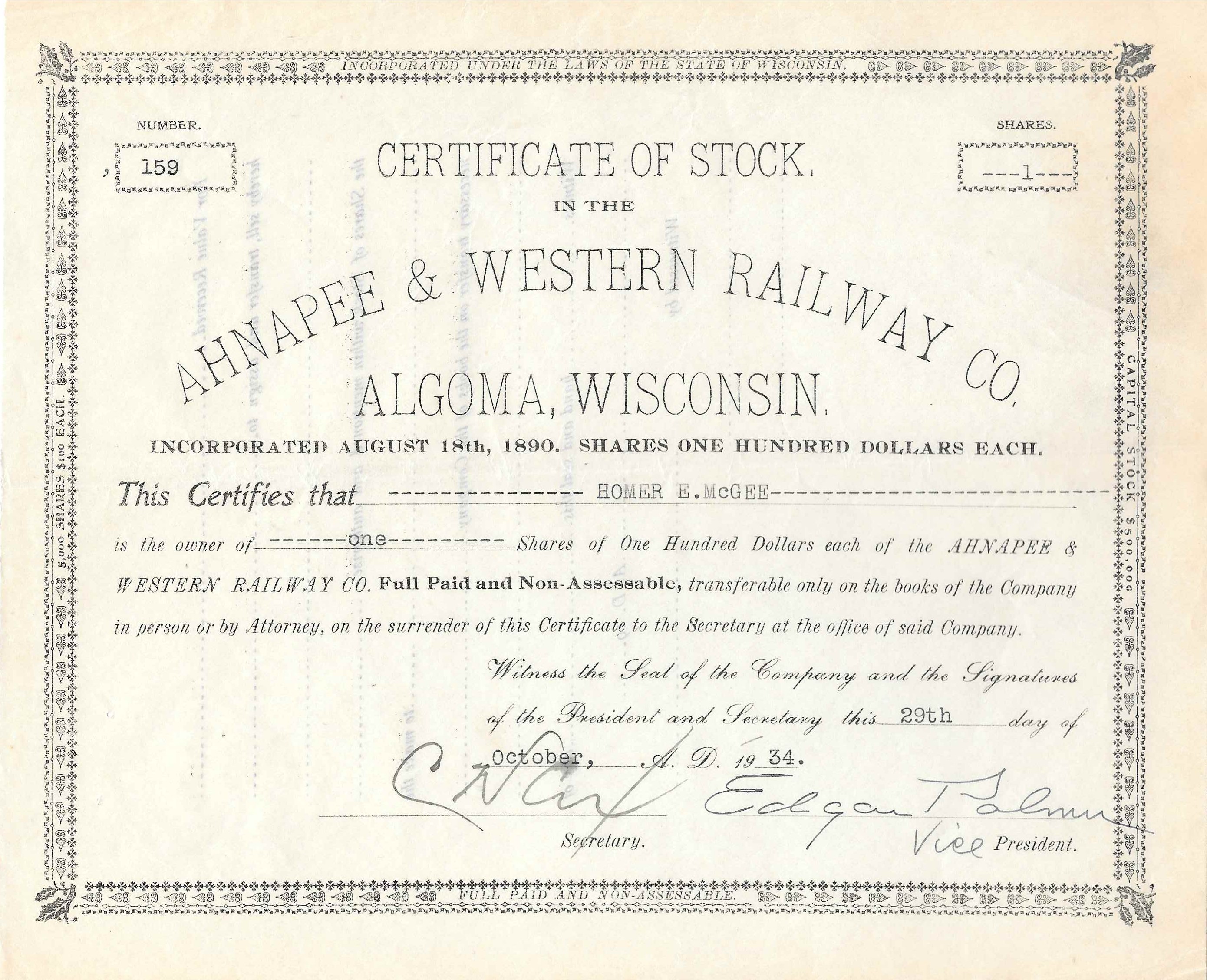

There have been a handful of banks in the county. Commerce in the area was not advanced enough for there to have been any banks during the obsolete note era (1850-60s). There were no national banks in the county during the national bank issuing period (1863-1935).

Baylake Bank was the last bank based in the county when it was taken over by Nicolet National Bank in 2016. It was also the oldest bank in the county. It was founded as a private institution in 1889 as the Bank of Sturgeon Bay and received its state charter in 1891. It changed its name to Baylake Bank in 1994 when it merged with the Bank of Kewaunee.

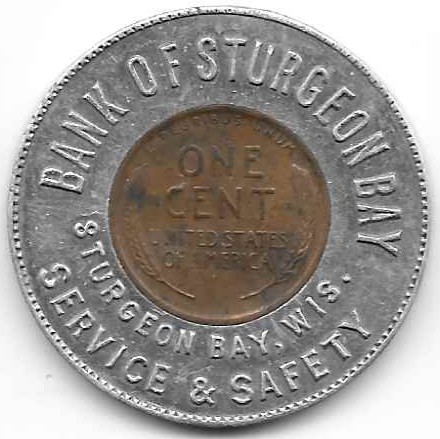

There are a handful of numismatic mementos of the Bank of Sturgeon Bay that span most of its history.

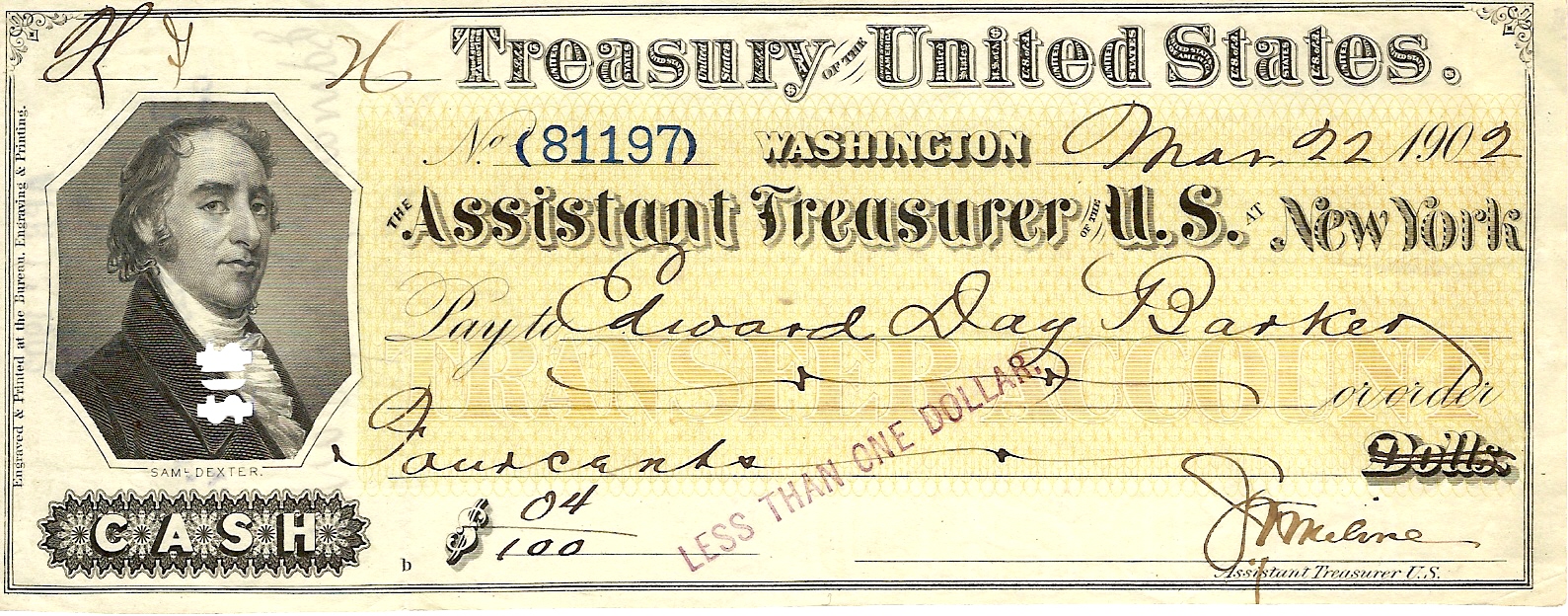

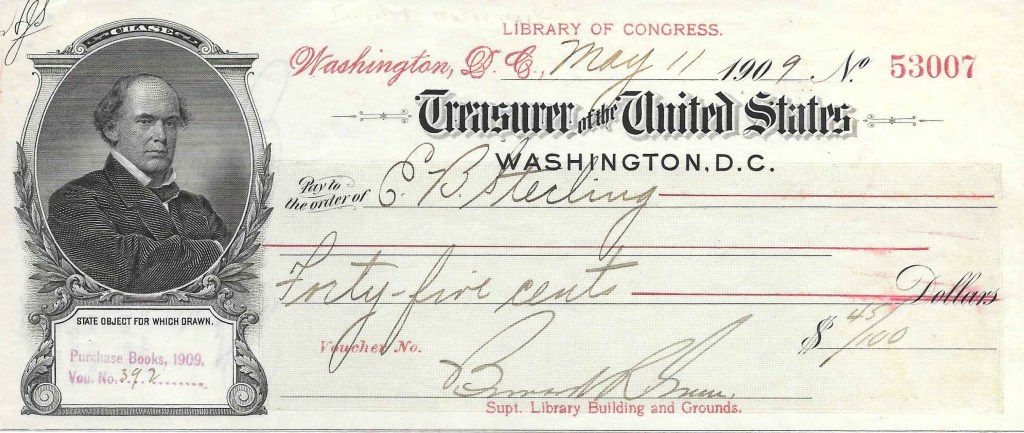

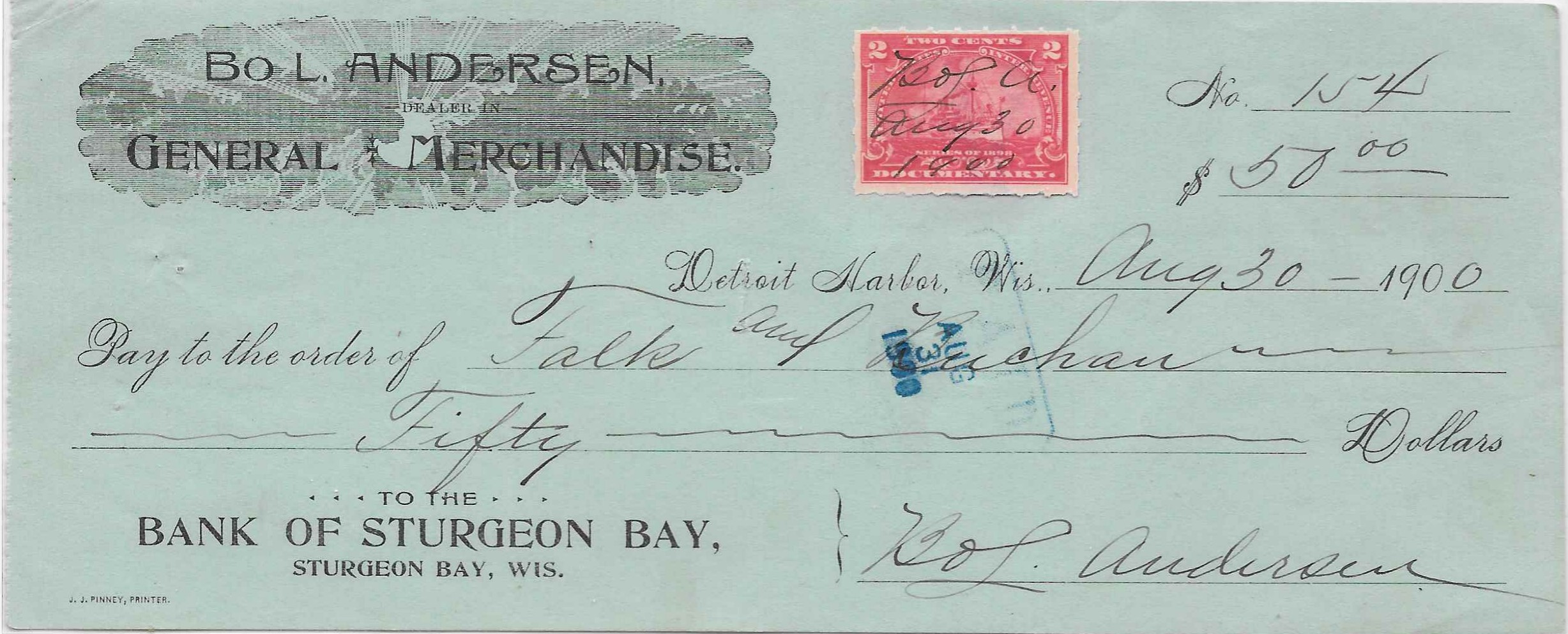

The earliest piece I have is this check written in 1900 on the account of Bo L. Andersen. It was printed by J.J. Pinney, a printer in Sturgeon Bay. It features a two cent documentary revenue stamp. A two cent tax was imposed on checks in 1898 to help pay for the Spanish-American War.

Andersen operated a general store on Washington Island off the northern end of the peninsula. The check has identifies his location as Detroit Harbor, Wisconsin which is the site of the island dock for the Washington Island Ferry. The payee is Falk & Buchan, a seed seller in Sturgeon Bay.

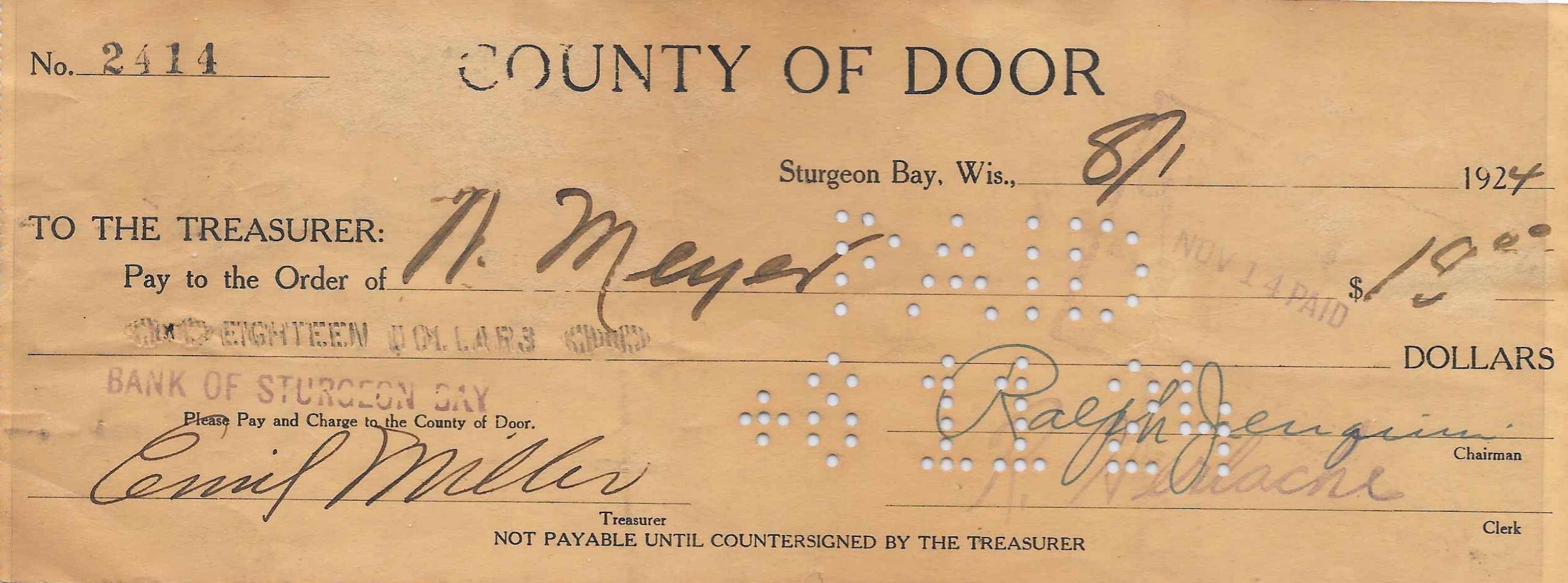

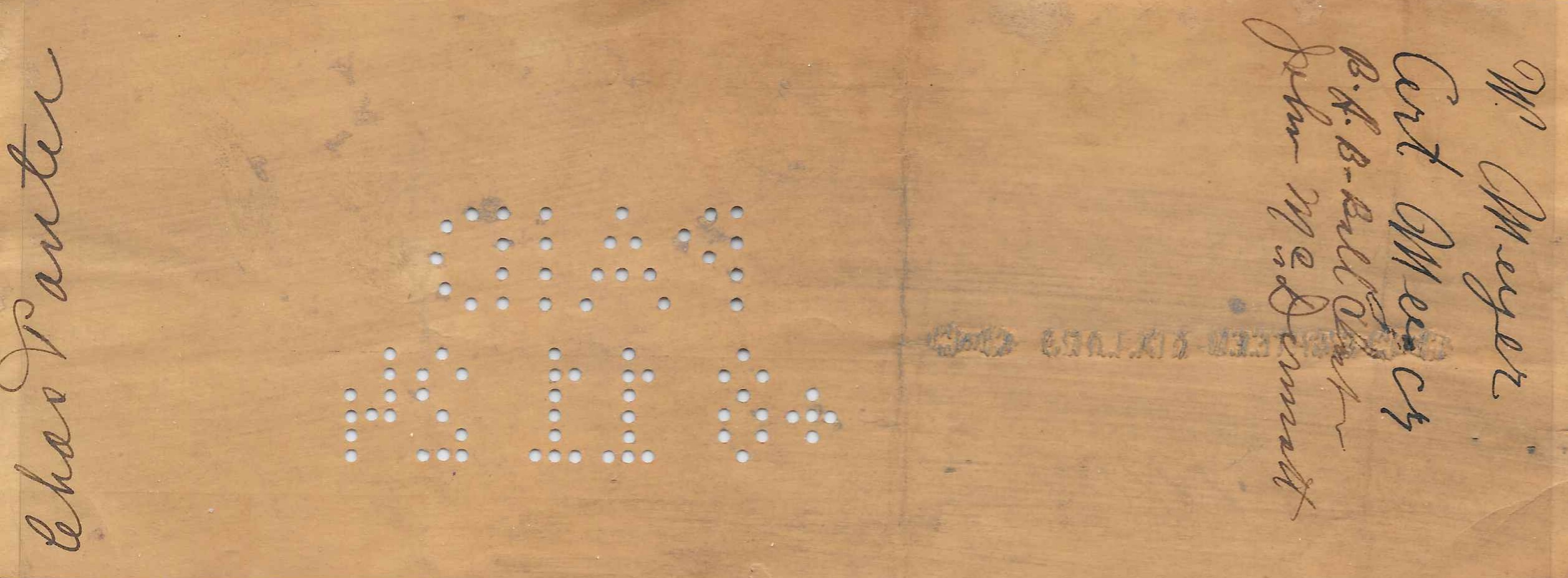

This check for $18.00 was written in 1924 by the Door County Treasurer and payable at the Bank of Sturgeon Bay. The multiple endorsements on the back shows the practice of passing negotiable instruments from holder to holder to pay debts. The check was written on August 1 and cleared the Bank of Sturgeon Bay on August 11 (shown by the perforated date). During that time it passed through five different hands.

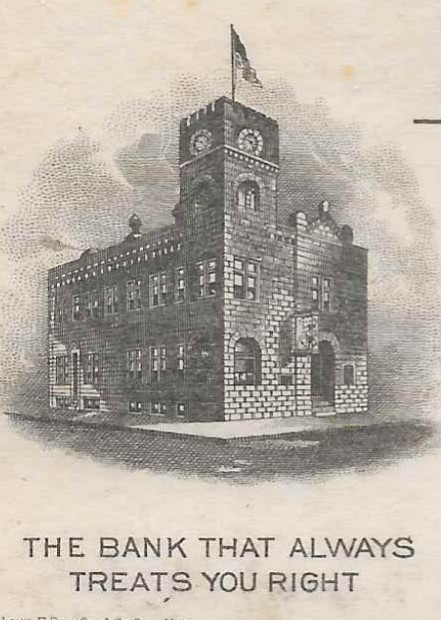

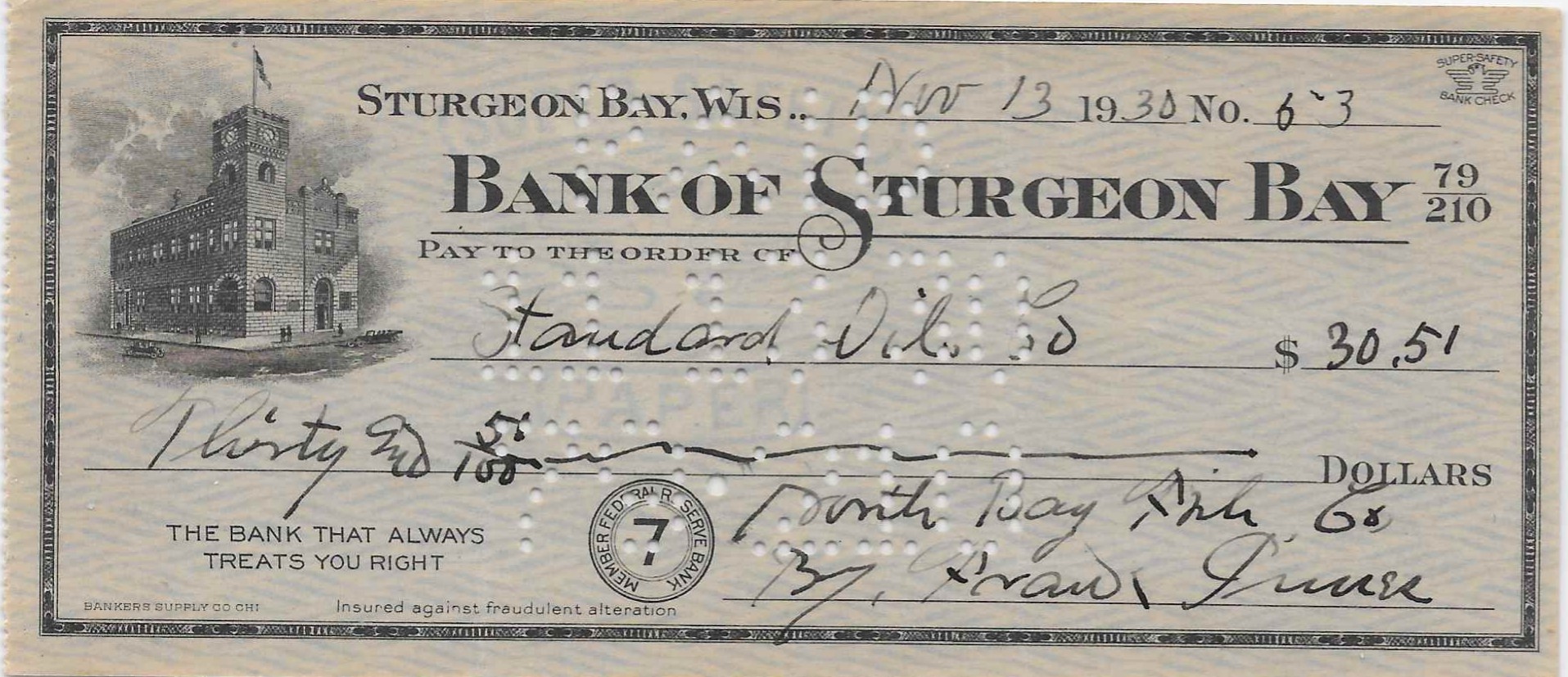

This next check was written in 1930 by the North Bay Fish Company. North Bay is located in the Town of Baileys Harbor about half way up the peninsula on the Lake Michigan side. The bank building is featured in the vignette at left. The building still stands although the clock tower was removed in the 1930s for safety reasons. The current bank location is two blocks away.

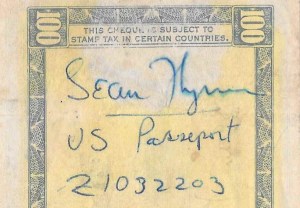

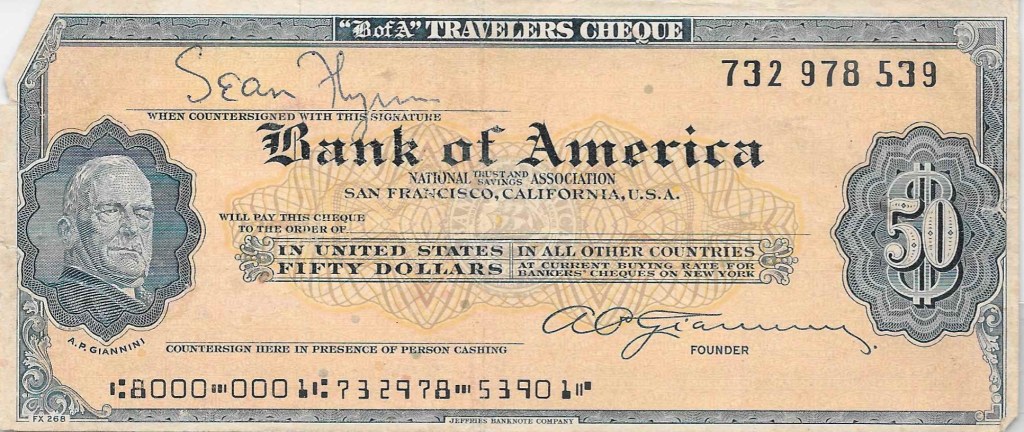

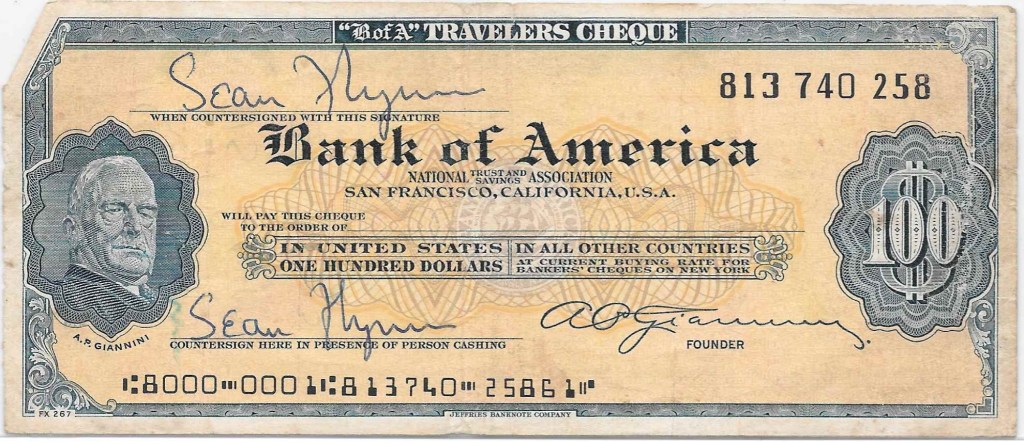

This piece is an uncashed travellers cheque issued by the First National Bank of Chicago through the Bank of Sturgeon Bay. Information on the back indicates it dates from the early 1960s. I was unable to verify the holders name.

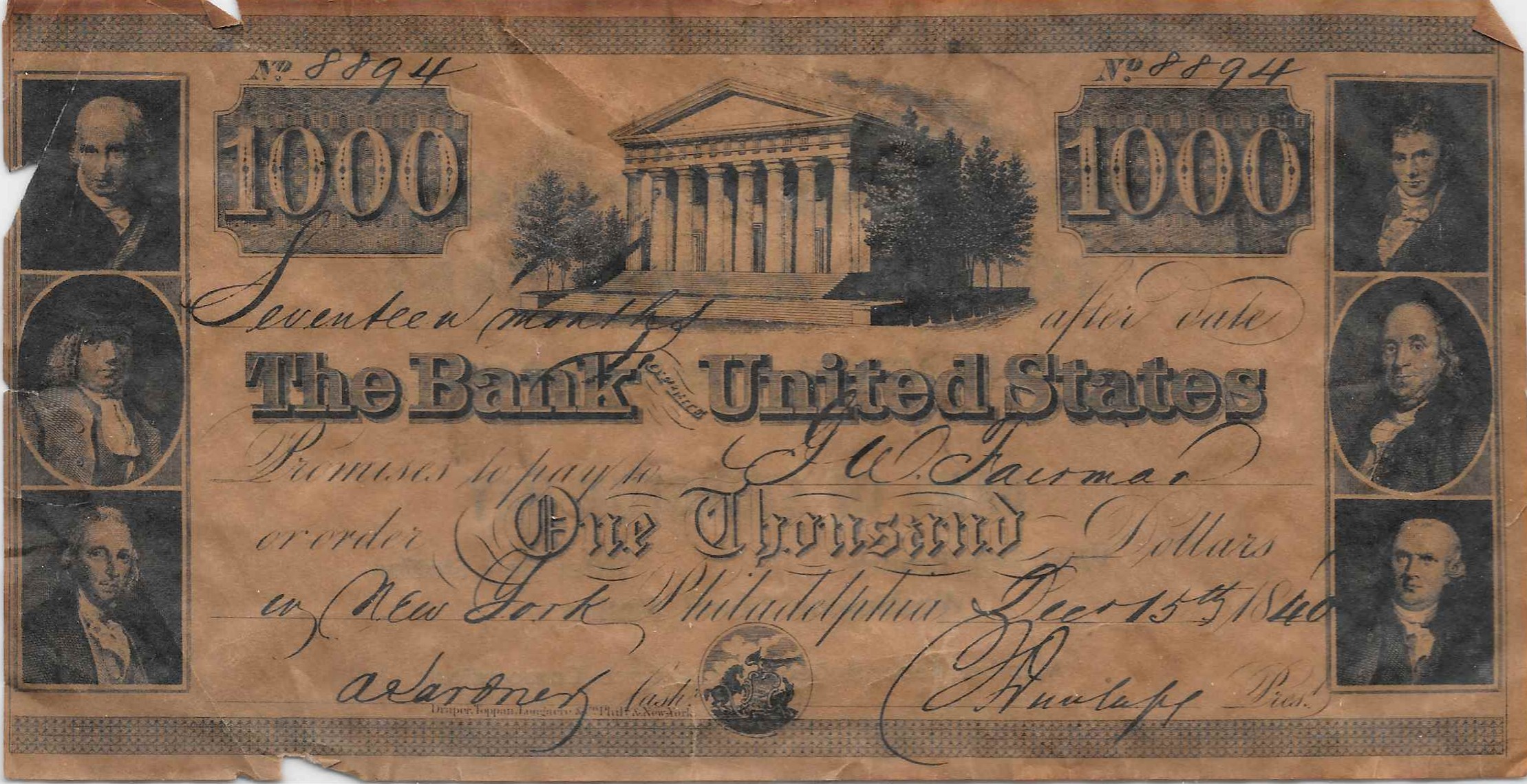

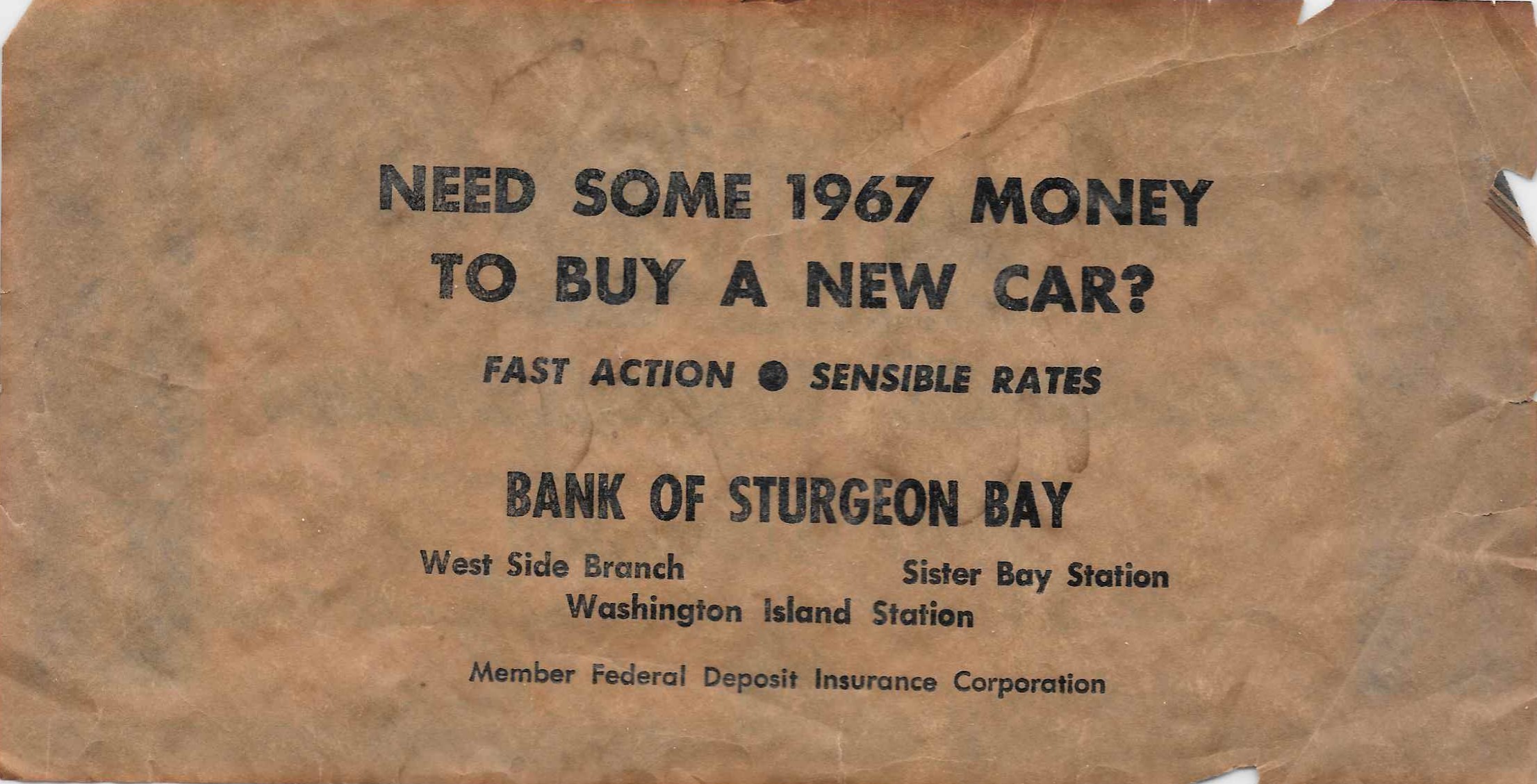

Paper money collectors will recognize this facsimile of a $1,000.00 post note issued by the Bank of the United States in 1840 with serial number 8894. It was an often duplicated piece used for advertising as it was here by the Bank in 1967.

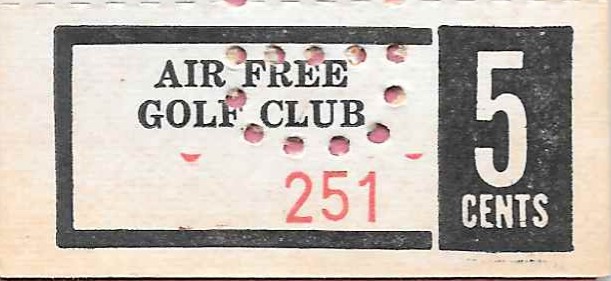

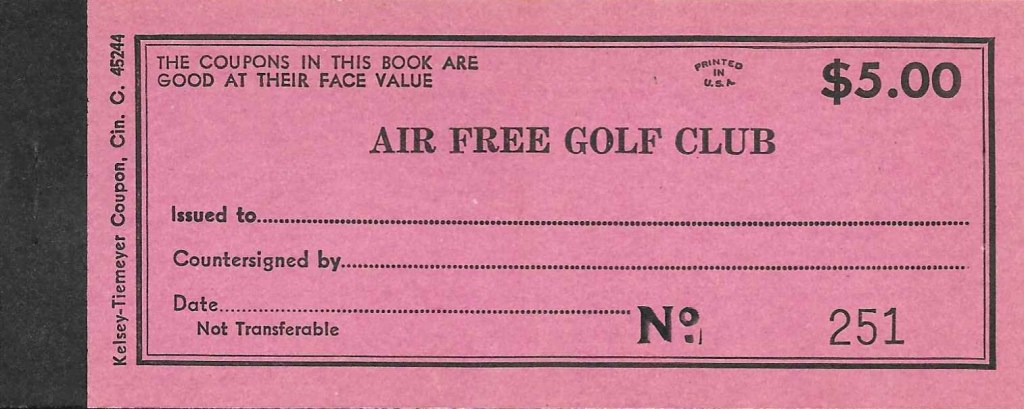

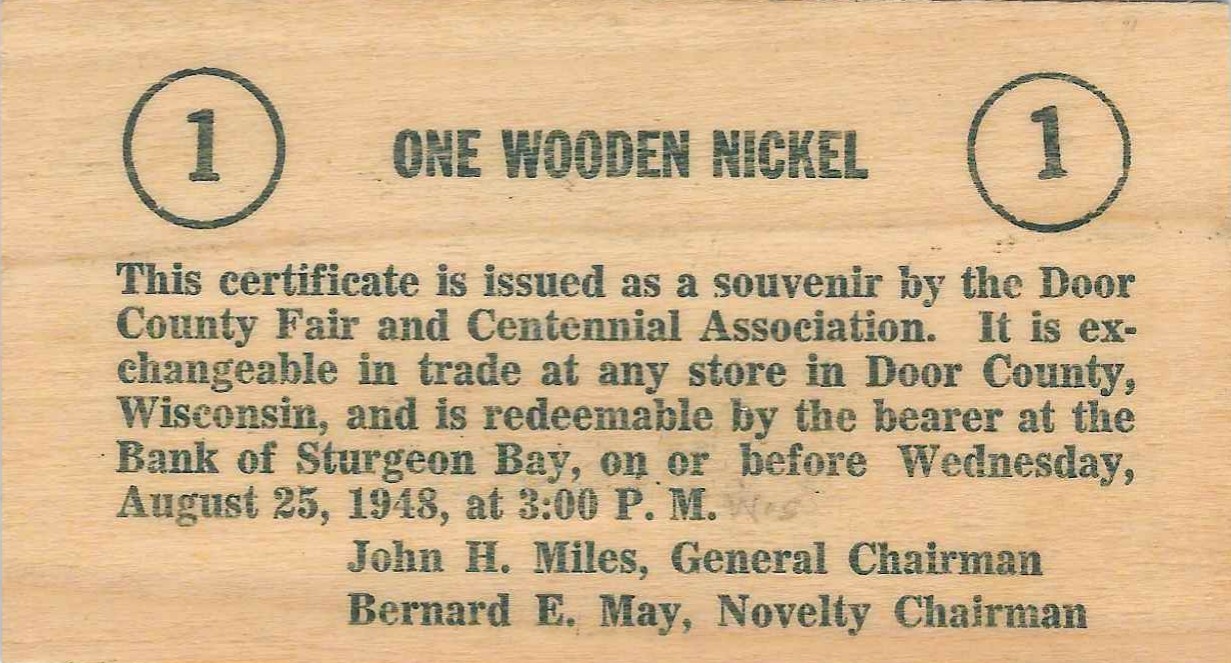

Door County celebrated its centennial in 1948. This wooden nickel is one of a series of three that were issued to mark the occasion. The others being worth two nickels and five nickels. It is redeemable at the Bank of Sturgeon Bay. Wooden nickels were popular souvenirs in the 1930s-50s. A not very accurate map of the county appears on the face.

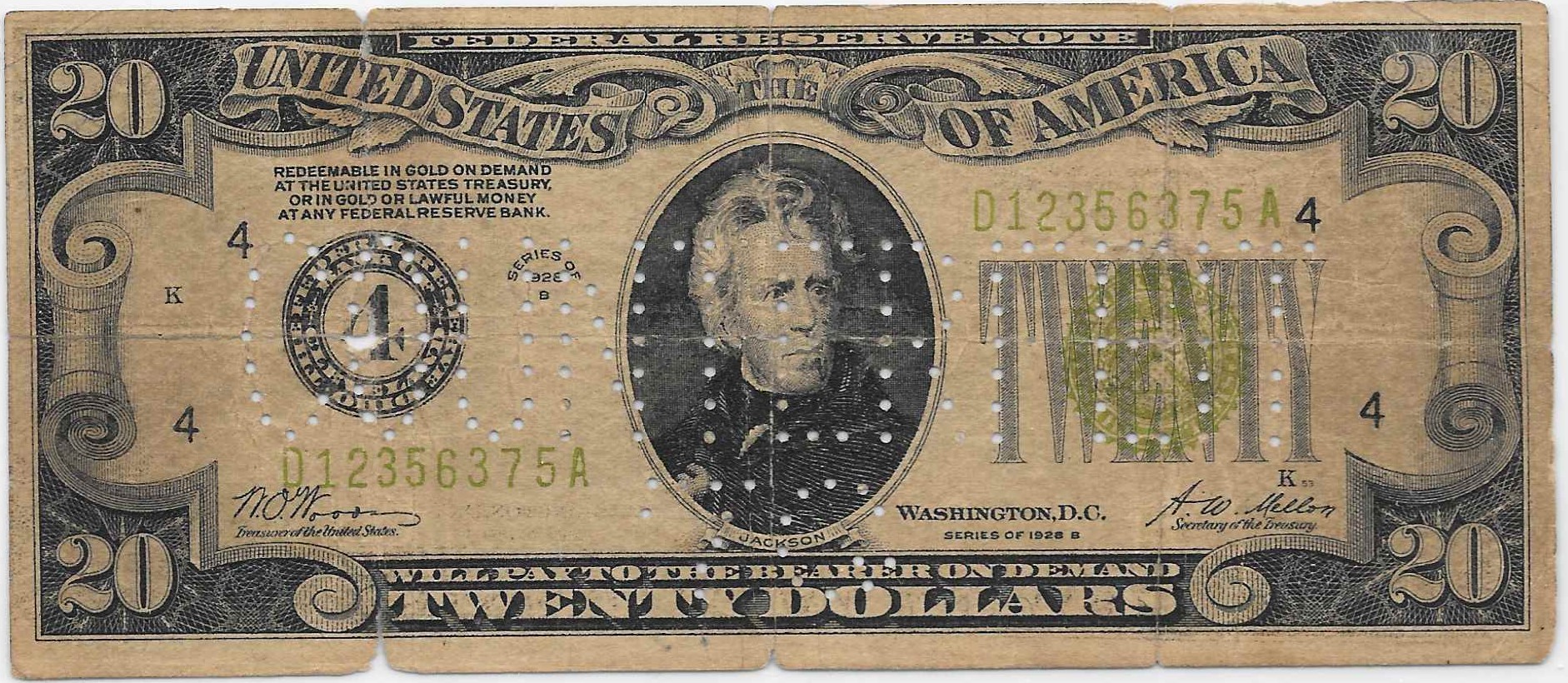

This final piece is not mine but belongs to a colleague. It is a counterfeit 1928B $20.00 Federal Reserve Note from the Cleveland Fed. The notation on the back indicates it was found at the Bank of Sturgeon Bay on July 22, 1936 and received by the Federal Reserve Bank (probably Chicago as Sturgeon Bay is located in the Chicago Federal Reserve District) the next day. The paper is not close to being correct and the aging of the note was artificial. The counterfeiters made a glaring mistake when they printed this note. The Federal Reserve Bank seal on the left side of Series 1928 and Series 1928A $20.00 notes had large numerals in them as this note does. But the design was changed for Series 1928B so that the corresponding capital letter appears in the seal (in this case D for the Cleveland Federal Reserve Bank).