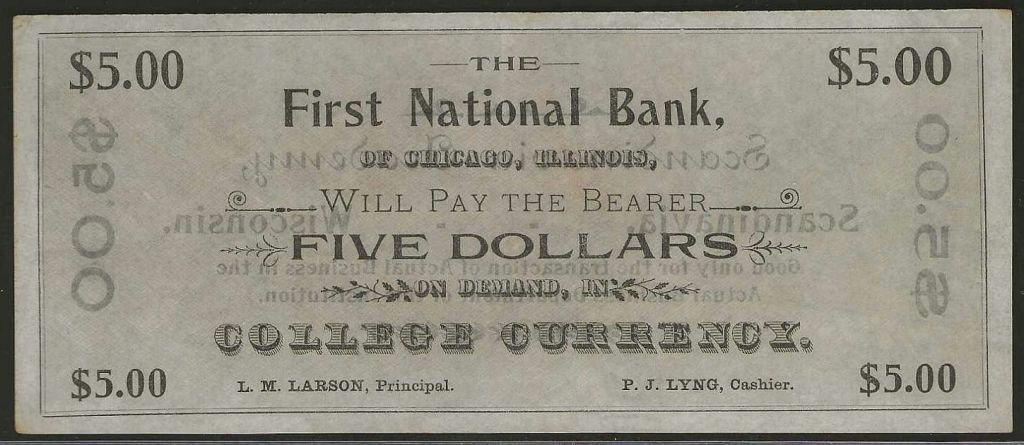

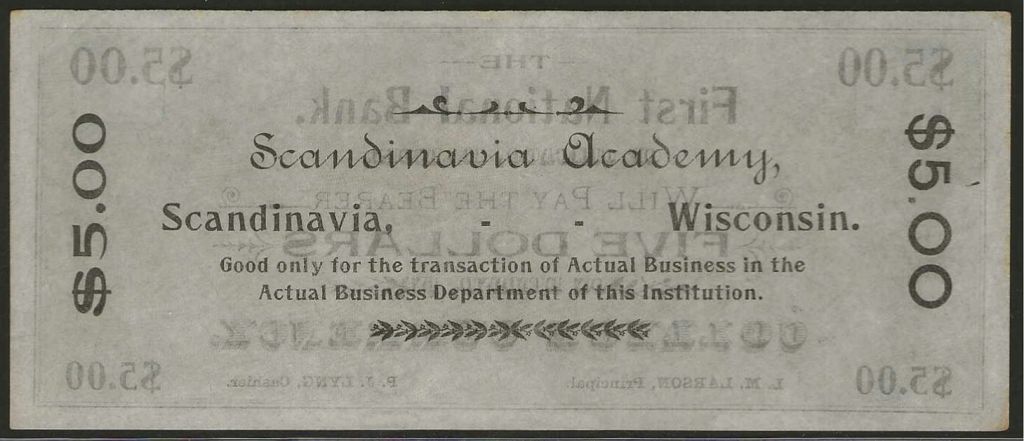

College currency is a type of practice paper money that at one time was used in business training schools. Most college currency dates from the late 19th Century. Many different schools printed college currency. The different types were cataloged by Herb and Martha Schingoethe in their 1993 treatment, College Currency, Money for Business Training.

The above note was printed for use in the Scandinavia Academy of Scandinavia, Wisconsin. The Academy was founded in 1891 by the United Lutheran Church in the small, central Wisconsin town in Waupaca County. The school’s first building was dedicated on Reformation Day in 1893 and opened for classes on November 1.

The school was to be an “educational institution on the High School plan, also offering a Business Course, whose atmosphere and general management should be permeated with christian principles and be conducive of a healthy and moral growth to those who should frequent the school.”

The original school building burned in 1919. It was rebuilt in 1921 and the curriculum was enlarged to include junior college classes. The name was changed to Central Wisconsin College to reflect this. That institution closed in 1932. The buildings then housed the local Union Free High School and are still standing.

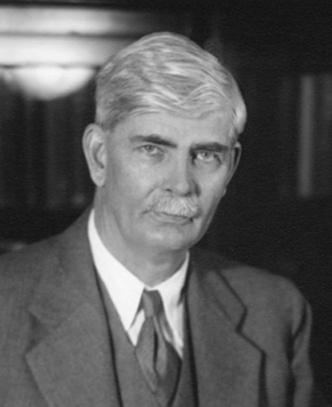

The note identifies L.M. Larson as Principal and P.J. Lyng as Cashier. Laurence M. Larson was named the school’s principal in 1894. Larson was a Norwegian immigrant who attended Drake University. He left the Academy to attend further studies at the University of Wisconsin. In 1907, he was made a professor of history at the University of Illinois where he finished his academic career. He was a prolific writer concentrating on Medieval Norse and English history.

Peder J. Lyng was a graduate of the initial class from Concordia College in Moorhead, Minnesota in 1893. He was hired in 1894 to head the Commercial Department (the business school) at Scandinavia Academy. Tragically, he died in January 1895 at his home in Waupaca.

Lyng’s brief tenure at the school narrows the date of printing of the notes. In addition to the $5.00 note, a 50 cent and $1.00 note are also known. The 50 cent note is somewhat peculiar in that it is the same size as the higher denominations and fractional currency had ceased being printed in the United States in 1876.